The Threshold of Heaven: A Canadian Elder’s Journey to Find Himself in the Smara Desert

Not all who wander are lost. Some are searching.

This is the story of Alex, a Canadian traveler with Chinese roots, who journeyed from Marrakech to Smara—not for luxury hotels or Instagram photos, but for something deeper. What he found in the wadi, under a sky untouched by city lights, and in moments of profound silence, changed him.

This narrative, enhanced with touches of literary imagination, captures the essence of what a true desert experience offers: not entertainment, but transformation.

Welcome to Smara. Welcome to yourself.

The Threshold of Heaven:

The Tale of a Man Who Came from Afar to Find Himself Near

I. The Arrival

In that year when the world seemed noisier than ever before, an old man decided to search for silence.

His decision was not sudden, but rather the culmination of years of muted questions, the kind that accumulate in the chest like invisible dust that weighs down one’s breathing. He had reached an age sufficient to know that answers come neither from books nor from sages, but from places that force you to confront yourself without masks.

He came from Canada, that vast land where snow covers questions for six months of the year. He was Canadian by citizenship, Chinese by blood, Saharan by soul without knowing it. He carried a single suitcase, not heavy, for he had learned over the years that excess things do not fill the void but widen it.

He boarded the bus from Marrakech, that city that screams with its colors and scents and sounds. He sat by the window, watching Morocco transform from red to yellow to brown, from mountains to plains to desert. The scene resembled reading a geography book written in light.

In Laayoune, he descended quietly, did not ask about luxury hotels. He asked for the road to Smara.

“Why Smara?” the driver asked with genuine curiosity.

The old man smiled the smile of one who knows but cannot explain: “Because I have never been there before.”

II. The Wadi

The desert is not a place, but a state of being.

This is what he realized when he arrived at the wadi, where they took him away from the town, to where urbanization ends and true existence begins. There was no paved road, no signs guiding tourists, no guidebook explaining “the top ten points to visit.” There was only the horizon, that illusory line separating earth from sky, or perhaps uniting them.

He sat on the sand with difficulty, his knees protested a little, but his spirit was light. Before him, an old acacia tree resisted time in silence, its roots diving deep into the earth’s interior searching for water that might not exist. He looked at it for a long time, and saw himself in it.

“How old are you?” he asked the tree in a low voice.

It did not answer, but he heard the response in the rustle of its sparse leaves.

When they lit the fire, the people gathered around it with complete spontaneity, no false ceremony or playing the role of hosts. They were there, simply, like the sands and the stars. They handed him tea in a small glass, hot, sweet, with something of bitterness too.

“Saharan tea is not a drink,” one of them said while pouring the second glass, “it is a ritual, time, conversation without words.”

The old man sipped slowly. He remembered his Chinese father, how he would prepare tea in Toronto with the same reverence, as if practicing a religious rite. “Tea teaches you patience,” he used to say. “Hot water alone is not enough, you need time.”

III. The Sky

When night fell, with it came a sky he had never seen before.

Not because it was different, but because he had never truly looked at it before. In cities, the sky is merely a blue or gray ceiling, decorated with some bright dots if you are lucky. Here, in this place that has no name on maps, the sky was everything.

He raised his head, and for the first time in decades, felt dizzy. Not the dizziness of illness, but the dizziness of wonder, that which strikes those who stand at the edge of the universe and look at its vastness.

The stars were not distant points, but present, witnessing, pulsing. The galaxy stretched like a river of light, and the moon sailed slowly like an ancient ship that knows its destination. The scene transcended beauty to something else, something for which there is no word in any language.

“This is the first time I see the moon this close,” he whispered, his voice nearly lost in the great silence.

“Here,” said his host, “the sky is not far away, we are the ones who moved away.”

They sat in silence for a long time. It was not an awkward silence, but the silence of comfort, the silence of those who do not need to fill the void with words. The fire crackled, the wind whispered, and the universe rotated above them without hurry.

At some moment, he saw a shooting star pierce the sky and disappear.

“Did you make a wish?” one of them asked with a smile.

He shook his head: “I no longer wish for anything. I am here.”

IV. The Crossing

An hour before dawn, something happened that he did not know was possible.

The moon still hung on the western horizon, full, silvery, majestic. And at the same moment, the sun began to peek from the eastern horizon, golden, warm, promising. For a few brief moments, night and day gathered in the same sky, moon and sun, coldness and warmth, ending and beginning.

He stood transfixed. The scene was too large to be contained by the eyes, so it entered directly into the heart.

“This is rare,” said his host. “To see the moonset and sunrise at the same moment. We call it ‘The Crossing.'”

“The Crossing,” he repeated the word slowly, tasting it. “From what to what?”

“From night to day, from past to future, from your old self to your new self.”

He remained standing until the scene was complete, until the moon disappeared entirely and the sun rose. He felt something move in his chest, something that had been frozen for a long time began to melt.

Tears, of which he was not ashamed, rolled down his cheeks.

“My father told me once,” he said in a trembling voice, “that the desert returns to a person what the city has stolen from him. I did not understand what he meant. Now I understand.”

V. The Town

In the morning, he walked with them to the town.

It was not a tourist place in the traditional sense. There were no souvenir shops selling the same things made in China and claiming they are traditional. There were no restaurants serving a diluted version of local food to please tourist palates. The place was real, and that is what made it exceptional.

He entered homes, sat with people, drank tea countless times. Children approached him with curiosity, touched his white beard, laughed at his pronunciation of Arabic words. He did not feel alien, but rather a strange belonging.

In someone’s house, he saw a hand-woven carpet, its colors bold yet harmonious, red and orange and green and black and white, complex geometric shapes telling stories he did not know.

“This was made by my grandmother,” said the host, “every line in it has meaning. This shape symbolizes water, this one the tent, and this one the road.”

He touched the carpet with his fingers, felt the roughness of the wool, the time woven into every knot.

“In Canada,” he said, “we buy carpets from stores. Here, carpets tell stories.”

VI. The Transformation

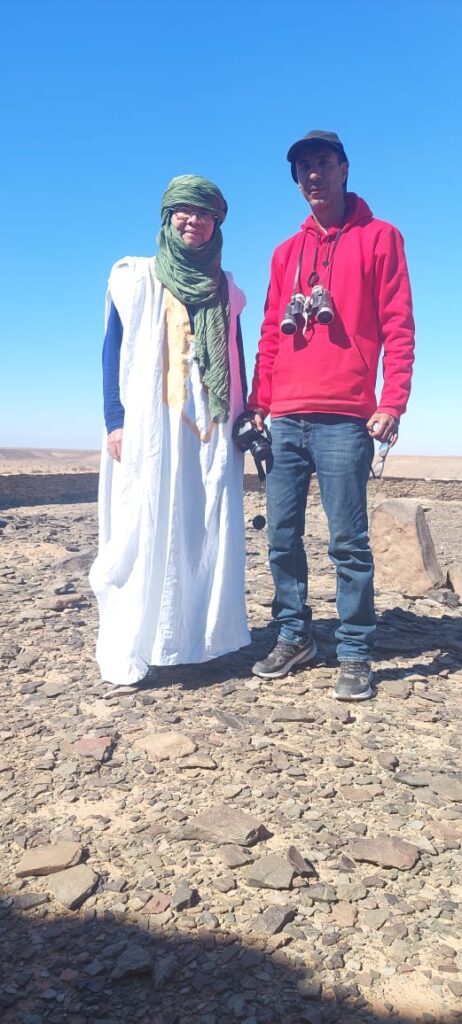

On the second day, they dressed him in traditional attire.

The loose white daraa, and the green turban. He stood before the mirror, and did not recognize himself. Or perhaps he recognized his true self for the first time.

“How do you feel?” they asked him.

“I feel light,” he said. “As if the clothes I had been wearing all my life were heavier than I thought.”

They led him to the place where traditional fabrics are woven, walls of colored cloth, a ceiling of textiles. He stood before a background decorated with colors that looked as if they had been pierced by a mad rainbow, and smiled.

They took a picture of him. He looked at it in the camera, and saw another man, a free man.

“I will send this to my grandchildren,” he said. “I will tell them that their grandfather went to the desert and found something he was searching for without knowing its name.”

VII. The Tree

On the last day, he returned to the acacia tree.

He stood before it for a long time, placed his palms on its rough trunk, closed his eyes.

“Thank you,” he whispered.

For what was he thanking it? He did not know exactly. For the shade perhaps, for the resilience, for the staying, for the existence despite harshness.

“In Canada,” he said to his companions, “we plant trees in our organized gardens, water them regularly, prune their branches, protect them from the cold. And in the end, when a strong storm comes, they fall.”

He looked at the acacia: “This tree, no one waters it, no one protects it, no one prunes it. Yet it has been here for hundreds of years. I learned today that true strength is not in protection, but in the ability to resist.”

VIII. The Farewell

When it was time to leave, he did not feel enthusiasm about returning.

He stood at the edge of the wadi, looking at the horizon he had learned to read. The desert was no longer just sand, but had become a language, and he was beginning to understand its letters.

“Will you return?” they asked him.

“I do not know,” he said honestly. “But I will not truly leave. Something of me will remain here, and something from here will go with me.”

He shook hands with them one by one, long embraces, few words. Words were not necessary, silence was more eloquent.

On the bus, he sat by the window again. But this time he did not look at the outside scene, but at his reflection on the glass. He saw a different man, a lighter man, more peaceful, closer to himself.

He took out a small notebook from his pocket, and began to write:

“I went to the desert searching for silence, and found true conversation.

I went searching for emptiness, and found fullness.

I went searching for myself, and found that I had been there all along, only I was looking in the wrong direction.”

IX. The Ending That Is Not an Ending

Months later, a letter arrived in Smara.

It was from Canada, from the old man. Inside the envelope, a photograph he had taken of his grandson looking at the sky on a clear night, and a note written in trembling handwriting:

“I taught my grandson to look at the stars. I told him about the place where you can see the moonset and sunrise at the same moment. He said to me: ‘Grandpa, is this real?’ I told him: ‘More real than anything else in this world.’

He will come one day. And when he comes, he will not be a tourist, but a pilgrim. Because some places are not destinations, but crossings. And some journeys are not movement in space, but movement in the soul.

Thank you for not selling me a tourist experience, but granting me a real moment in a world that grows more false each day.”

In Smara, they do not offer tourist programs wrapped in lights and false promises.

They open a door for you, and you are the one who chooses what you see beyond it.

Some see a desert.

Others see themselves.

The End

“Not all roads lead to Rome. Some roads lead to yourself.”

— Saharan proverb (perhaps)

Said Legbouri

Social

This is what we offer in Smara: not a tourist package, but an opening—a threshold to cross.

Some see a desert. Others see themselves.

Ready for your own crossing? [Contact us]